A blast of wind pushes me forward, slamming me against the rocky path’s edge. The partition is only around five inches high and my heart races as I eye the 305-meter drop to the sparkling Aegean. Determined, I turn to tackle the rest of the 295 snaking stone steps, and catch a glimpse of a white dot on the craggy cliffs.

The painted sliver I see glued to the rock is Panayia Khozoviotissa, a Greek Orthodox Monastery built in 1088. I am on Amorgos, the eastern most of the Cyclades Islands and I’ve endured the nine-hour ferry ride from Athens specially to see this architectural wonder.

The monastery is five yards wide and eight stories high. From a distance, it looks like a white-gloved fist, clamped tightly on a rugged wall.

Khozoviotissa embraces the organic tradition of Greek monasteries, harmonizing and blending with its surrounding landscape.

It takes me a supernatural amount of energy just to reach it. By the time I get to the top, I’m disheveled and wheezing. My friend Anthony Vlavianos, a 78-year-old Athens-based architect and photographer who has accompanied me on this jaunt, is unfazed.

Vlavianos, who summers annually on the 47-square-mile island where his parents were born, is going to introduce me to the monastery’s head monk, Father Spiros, whom he has known since he was a boy.

“Every step up is a step closer to God,” he says, nodding toward the final few steps to the entrance. Apparently it was even more difficult some years back. “You used to have to climb a movable wooden ladder up to the door,” he explains.

The entire monastery is a hodge-podge of add-ons and embellishments.

The three-foot-tall high wooden door is topped with a gothic arch, a signature of the Venetians who occupied the island in the 15th century. The door’s carved marble jambs were added during the 1686 renovations.

The Greek juniper beams projecting from the northeast wall may have been here since the beginning. However, the front entrance hall looks relatively new. Squeezing through the minuscule entrance, I find myself in a whitewashed hall furnished with wooden chest and plaque commemorating the original founder, Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus who ruled from 1081-1118.

A narrow staircase hewn from the rock winds upward and at the top stands a priest in black cassock and cylindrical hat. He glares at me. “Ladies must wear a skirt. Show respect,” he says in choppy English.

Luckily, I have a shawl in my bag, which doubles as a sarong-style skirt. I scuttle down to the landing and wrap it around my middle then inch back up the stairs. The priest nods in approval, not seeming to care about my jeans poking out below.

He is one of the three resident monks, a far cry from a century ago when 100 lived here. He leads us up more rock steps to the sitting room. Portraits of past bishops line the walls, and a small brass chandelier lights the space.

I perch on the crushed red velvet couch and an assistant arrives with a tray of sugar-dusted sweets and Greek coffee. There are also small glasses of psimeni, a type of Amogos brandy. I take a sip of the honey-infused spirit and a cinnamon-spiced warmth spreads through my body. Delicious.

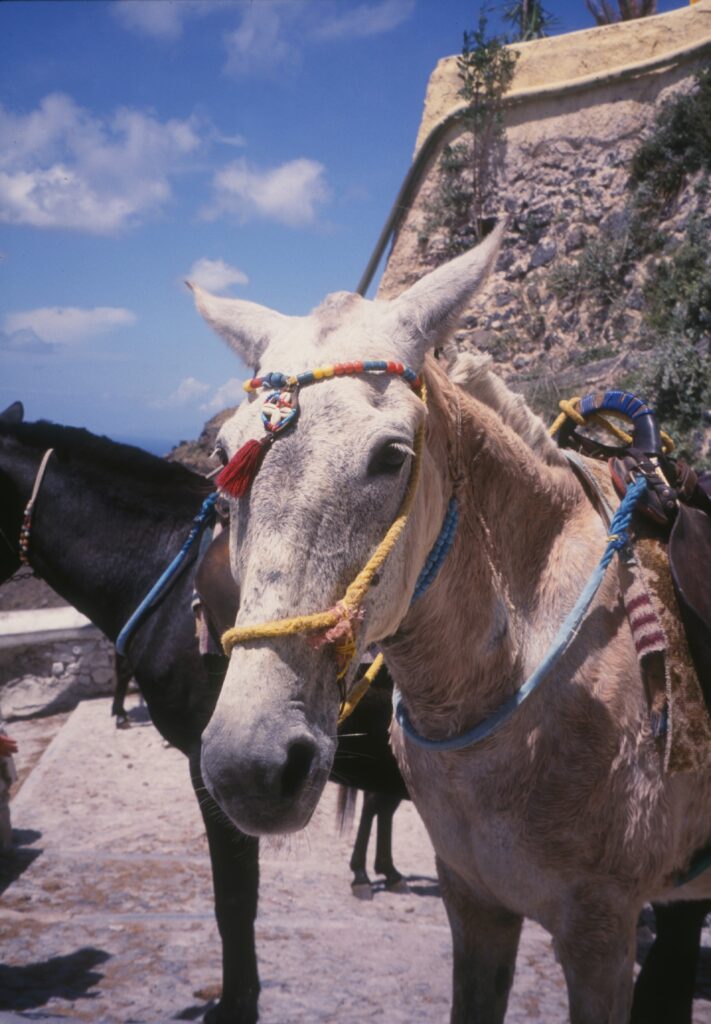

“Years ago,” Vlavianos says, “there was no electricity and water had to be hauled up with donkeys.” He points at a whitewashed cubbyhole on the same level as the sitting room with a small stove and sinks complete with working faucets. “There’s running water now, but donkeys still carry in the supplies,” he says.

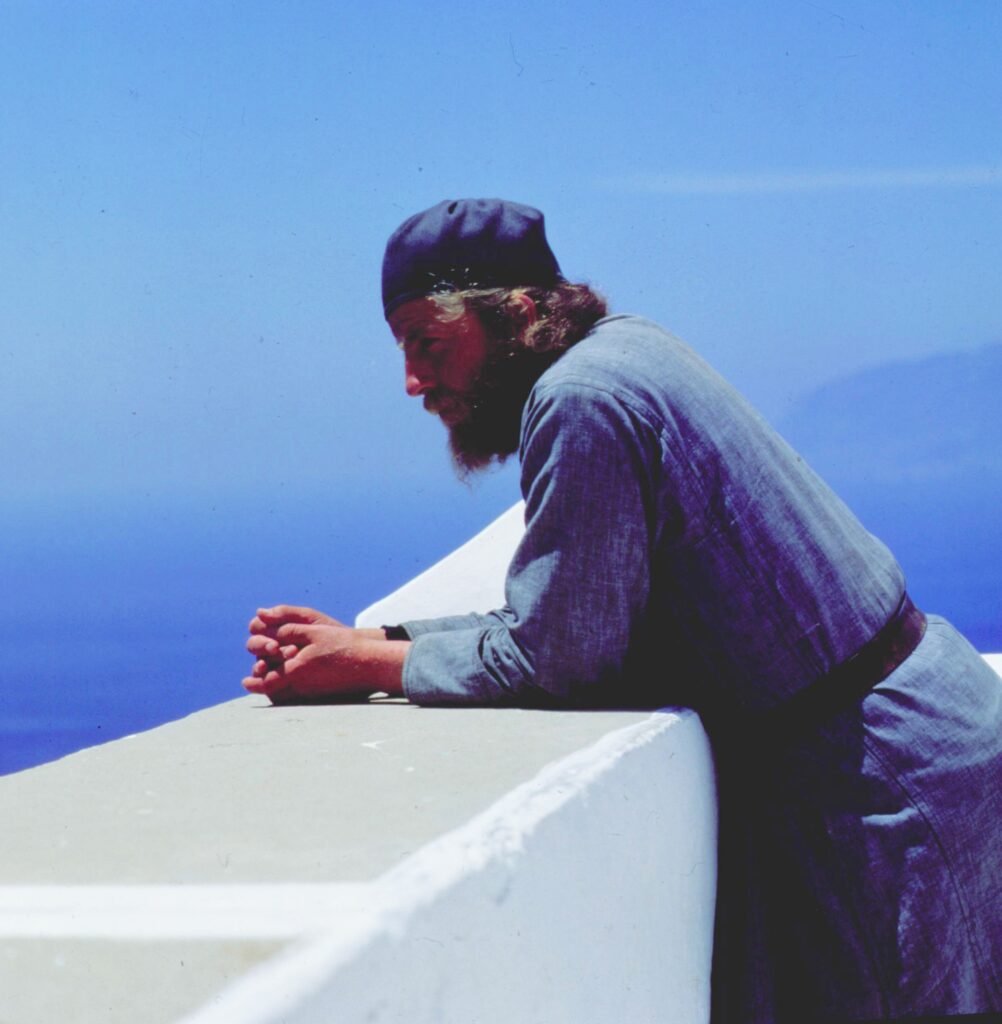

A rumble of laughter erupts from below, followed by the sound of rustling robes and heavy steps. A sun-weathered face with fly-away beard emerges from the narrow staircase.

“Papas Spiros! How are you?” Vlavianos exclaims, jumping from the couch and clasping his hand. Although Father Spiros doesn’t speak English, he smiles broadly and gestures for us to follow for a tour.

He leads us to the original kitchen, now a storage space for construction materials – planks of wood and tools. The beehive oven, no longer in use, is stacked with sheets of drywall.

“Rockslides. They happen all the time and they have to do repairs,” Vlavianos explains. Another room is piled high with thin mattresses. “Those are used on the feast of the Presentation of the Virgin every Nov. 21. People come from all over the island and many stay overnight.”

Vlavianos and I follow Father Spiros into the chapel, which is about two meters wide and four-and-a-half meters long. It’s where the most precious possession resides, an icon known as the “Panayia,” or Holy Virgin.

The icon, Vlavianos tells me, is said to have come from Palestine, from the Monastery of the Most Holy Virgin of Khoziba. It was carried to Cyprus by Christians who were persecuted by Arabs in the ninth century, then smashed in two by iconoclasts and thrown out to sea where a current transported it to the foot of Mt. Prophet Elijah.

The pieces were rejoined, and a small church was built in honor of the miracle. In 1088, Emperor Alexius Comnenus had the monastery built in the same spot.

In a dimly illuminated corner, the icon is hidden under a worn silver cover and surrounded by an ornately carved wooden frame. A case stuffed with watches and pendants sits nearby.

“Given in thanks by those who have had their prayers answered,” whispers Vlavianos. Every Easter and for the full week after, the priests take the icon on a procession around the island.

Like the history of the icon, the building of the monastery is steeped in miracle and mystery. No one knows who the builders were, the only clue is a chisel inside a glass case tucked in a chapel alcove.

“The story says that each night the master builder would leave his tools in one spot and in the morning, they would be found hanging on a nail in another spot,” says Vlavianos.

I spy the spike on a pillow in one of the cases.

Father Spiros leads us out to a balcony that seems to hover in space, high above the glistening Aegean. The priest leans on the balcony ledge and looks out at the sea. The brilliant blue merges into the horizon, and water and sky, free of boats and airplanes, seamlessly become one. The effect is disorienting and magnificent. Civilization has vanished.

“What is it like to live in such a place?” I ask.

Father Spiros turns and his arm sweeps past the cliffs, the whitewashed walls of the monastery and out towards the sea. His blue eyes twinkle and his hearty voice echoes off the rocky backdrop. Vlavianos translates.

“Perfection.”